Anne Schwartz

Environmental Writer

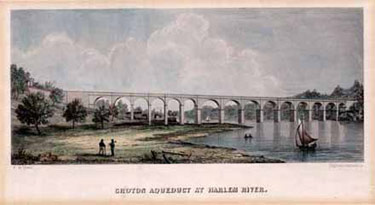

Reopening the 19th Century High Bridge

At one time, the High Bridge was known far and wide. Built in 1848 in the style of a Roman aqueduct, it carried water across the Harlem River. It was the most visible symbol of the city’s first water system, an engineering masterpiece that supplied abundant, clean water to a population previously dependent on fouled wells and subject to the twin scourges of disease and fire. Today, however, most New Yorkers have never heard of the High Bridge. Connecting Washington Heights Heights to the Bronx neighborhood of High Bridge, north of Yankee Stadium, it has been closed for decades, a forgotten historical footnote and a missing link between two communities

So it is fitting that the bridge, which helped New York City prosper into the 20th century, should play a role in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s blueprint for making the city sustainable into the 21st. One of the specific environmental and infrastructure goals of PlaNYC 2030 (and one that doesn’t need the approval of the state legislature) is reopening the bridge. The city has allocated $60 million for the project, in addition to an expected $12 million in federal funding. When complete, the reopened High Bridge will be an asset not only for the neighborhoods at both ends of the structure but for the entire city.

The Rise and Fall of the High Bridge

With its 100-foot-high stone arches crossing from cliff to cliff over the Harlem River Valley, the High Bridge quickly became a popular attraction. The pipes were decked over, and a walkway was added. People flocked to what was then the countryside to spend the day along the river and promenade across the bridge dressed in their finest clothes. A tourist industry sprung up with a ferry landing, beer gardens and inns. Boathouses, marinas and rowing clubs lined the river.

The city eventually expanded up both sides of the Harlem River, but parks were created where the bridge landed. The Manhattan side features the 116-acre Highbridge Park, which has a swimming pool on the site of an old reservoir and a recreation center. In the Bronx, a one-acre park of the same name overlooks the bridge and the wooded hillside across the river. When the water pipes were taken out of service in 1958, then-Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had the bridge itself transferred to the parks department.

The neighborhoods around the bridge declined and sometime around 1970, the city closed the High Bridge because of safety and maintenance concerns. (There is no evidence, however, to support the story that it was closed because kids threw rocks onto the Circle Line.) No one seems to have noted the date that a parks employee padlocked the gates for good.

Keeping the Dream Alive

Practically from the moment the bridge closed, Bronx and Upper Manhattan residents started trying to get back their river crossing. Around the city and within the parks department, too, people worked to promote the idea of reopening the bridge.

Ellen Macnow, coordinator of interagency planning at the parks department, has been one of the bridge’s most persistent advocates. “It happens to be, when you see it, a really fabulous place,” she said. “It reeks of history.” Macnow said that the effort to reopen the bridge first got traction with the 1993 New York City Greenway Plan, a proposed 350-mile network of pedestrian and bicycle trails that included the High Bridge.

Discussions between the parks department and the Department of Environmental Protection, which owns the now defunct water pipes inside the bridge, eventually led to a study by the Department of Transportation to determine the cost of restoring the bridge. Word spread, and more groups became involved. In 2001, the parks and environmental agencies and a number of nonprofit organizations working to improve the parks and trails in the area, including New York Restoration Project, Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct, and the City Parks Foundation formed the High Bridge Coalition.

A key to the effort was getting the residents of the two neighborhoods involved. In 2003, Partnerships for Parks, a joint program of the City Parks Foundation and the parks department, chose the High Bridge area as one of its Catalyst for Neighborhood Parks sites. This effort, focusing on neighborhoods with problematic parks, provides private funding for activities and events that in turn build community involvement in the parks and so help them attract additional public and private resources.

Joseph Sanchez, the Highbridge project coordinator, grew up in Washington Heights and recalls that, even as a child, he saw the potential and beauty in the local parks, “as ugly and dirty as they were.” To get people into the parks, he organized hikes, clean-ups and other activities, and brought in community groups to run sports and education programs. He also spread the word about the High Bridge and urged residents to join the effort to reopen it. “We began to hear stories from residents about how they once used the bridge, how they still want to use it,” said Macnow. Community members joined the coalition and began pushing to get the bridge restored.

In November 2006, the parks department announced that it would take the first steps toward opening the bridge, with a $5 million allocation of federal transportation money from U.S. Representative Jose Serrano and $1.5 million in city funding. But before the project was included in PlaNYC, coalition members thought it would take years to complete the repairs. “We are on our way to reopening the bridge much faster than we had ever thought,” said David Rivel, executive director of the City Parks Foundation. “It really just captured the imagination.”

The restoration will include repairing the bridge’s patterned brick walkway, its remaining stone arches and the steel span that replaced four of the stone arches in 1928 to allow boats to navigate the full width of the river. The bridge will also be safer than it was in its heyday with wheelchair ramps and higher fencing.

A Green Future for the Harlem River

Opening the High Bridge will bring multiple benefits. To begin with, it will make Highbridge Park, with its enormous pool and improved recreation center, more accessible to residents of the High Bridge neighborhood in the Bronx, who have few nearby recreational options. Even now, many Bronx kids climb over the bridge’s locked fences to get to the Manhattan side.

The bridge could also become the focal point of a revival of the Harlem River as a recreational destination, said Drew Becher, executive director of the New York Restoration Project, a private-public partnership founded in 1995 by Bette Midler to reclaim neglected parks in upper Manhattan and the Bronx. “It will make people look down and see what a great Harlem River Valley we have,” he said.

New York Restoration Project has contributed to the resurgence of boating on the river through its Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse, the first new community boathouse in New York City almost a 100 years. The organization recently planted 200 of an eventual 3,000 cherry trees along the river, which, they hope, will rival Washington, D.C.’s cherry blossoms in the spring.

Reopening the bridge also will promote the greenest and healthiest way to get around the city. It will become a vital link in city’s partially completed system of bike and pedestrian trails, including greenways being built on both sides of the Harlem River. It will also fill a gap in the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail, the 41-mile trail following the route of the city’s first water system.

And not least, the High Bridge is a unique recreational space in itself, a place that belongs only to pedestrians and cyclists, with magnificent views of the river and the cityscape. “A stroll on the bridge is just such an incredible thing,” said Joseph Sanchez. “You feel like you’re in the middle of the world.”